The prehistory of Papua New Guinea can be traced back to about 60,000 years ago when people first migrated towards the Australian continent. The written history began when European navigators first sighted New Guinea in the early part of the 16th century.

Archaeology

Archeological evidence indicates that humans arrived on New Guinea at least 60,000 years ago, probably by sea from Southeast Asia during an Ice Age period when the sea was lower and distances between islands shorter. Although the first arrivals were hunters and gatherers, early evidence shows that people managed the forest environment to provide food. There also are indications of gardening having been practiced at the same time that agriculture was developing in Mesopotamia and Egypt. Today's staples—sweet potatoes and pigs—were later arrivals, but shellfish and fish have long been mainstays of coastal dwellers' diets. Recent archaeological research suggests that 50,000 years ago, people may have occupied sites in the highlands at altitudes of up to 2000 metres, rather than being restricted to warmer coastal areas.[1]

European discovery

When Europeans first arrived, inhabitants of New Guinea and nearby islands - while still relying on bone, wood, and stone tools - had a productive agricultural system. They traded along the coast, mainly in pottery, shell ornaments and foodstuffs, and in the interior, where forest products were exchanged for shells and other sea products.

The first Europeans to sight New Guinea were probably the Portuguese and Spanish navigators sailing in the South Pacific in the early part of the 16th century. In 1526-27, the Portuguese explorer Jorge de Menezes accidentally came upon the principal island and is credited with naming it Papua, a Malay word for the frizzled quality of Melanesian hair. The term New Guinea was applied to the island in 1545 by a Spaniard, Yñigo Ortiz de Retez, because of a resemblance between the islands' inhabitants and those found on the African Guinea coast.

Although European navigators visited the islands and explored their coastlines thereafter, little was known of the inhabitants by Europeans until the 1870s, when Russian anthropologist Nicholai Miklukho-Maklai made a number of expeditions to New Guinea, spending several years living among native tribes, and described their way of life in a comprehensive treatise.

Territory of Papua

Main article: Territory of Papua

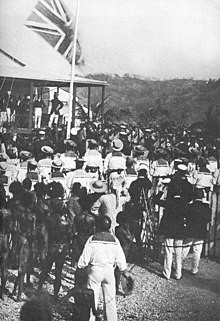

In 1883, the Colony of Queensland purported to annex the southern half of eastern New Guinea. On November 6, 1884, a British protectorate was proclaimed over the southern coast of New Guinea and its adjacent islands. The protectorate, called British New Guinea, was annexed outright on September 4, 1888. The possession was placed under the authority of the Commonwealth of Australia in 1902. Following the passage of the Papua Act, 1905, British New Guinea became the Territory of Papua, and formal Australian administration began in 1906, although Papua remained de jure a British possession until the independence of Papua New Guinea in 1975. Papua was administered under the Papua Act until it was invaded by the Empire of Japan in 1941, and civil administration suspended. During the Pacific War, Papua was governed by an Australian military administration from Port Moresby, where General Douglas MacArthur occasionally made his headquarters.

German New Guinea

Main article: German New Guinea

With Europe's growing desire for coconut oil, Godeffroy's of Hamburg, the largest trading firm in the Pacific, began trading for copra in the New Guinea Islands. In 1884, the German Empire formally took possession of the northeast quarter of the island and put its administration in the hands of a chartered trading company formed for the purpose, the German New Guinea Company. In the charter granted to this company by the German Imperial Government in May 1885, it was given the power to exercise sovereign rights over the territory and other "unoccupied" lands in the name of the government, and the ability to "negotiate" directly with the native inhabitants. Relationships with foreign powers were retained as the preserve of the German government. The Neu Guinea Kompanie paid for the local governmental institutions directly, in return for the concessions which had been awarded to it.

In 1899, the German imperial government assumed direct control of the territory, thereafter known as German New Guinea. In 1914, Australian troops occupied German New Guinea, and it remained under Australian military control through World War I until 1921.

Territory of New Guinea

Main article: Territory of New Guinea

The Commonwealth of Australia assumed a mandate from the League of Nations for governing the former German territory of New Guinea in 1920. It was administered under this mandate until the Japanese invasion in December 1941 brought about the suspension of Australian civil administration. Much of the Territory of New Guinea, including the islands of Bougainville and New Britain, was occupied by Japanese forces before being recaptured by Australian and American forces during the final months of the war (see New Guinea campaign).

Exploration of Mandated Territory of New Guinea

Akmana Expedition 1929-1930

‘The exploration of Papua–New Guinea has been a continuing process. Even today [April 1971] new groups of people occasionally are still contacted. Not until recent years has New Guinea’s exploration been planned; much of it has been the work of miners, labour recruiters, missionaries, adventurers, with different objects in mind. Many of these people have been doers, not recorders of facts, with the result that our knowledge of the territory’s exploration has not kept pace with the exploration itself.’ [2]

An exception is the record of the Akmana Gold Prospecting Company’s Field Party which carried out two expeditions from September to December 1929 and from mid February to the end of June 1930. [3] They journeyed on the "Banyandah", a cruiser of 38 feet (12 m) from Madang up the coast to the mouth of the Sepik River, travelling along that river to Marienberg and Moim, then along the Karosameri River to the Karrawaddi River and on to the Arrabundio River and Yemas, after which it was necessary to transport their stores and equipment by pinnace, canoe and ultimately on foot to their Mountain Base on the upper Arrabundio River.

During their first expedition the Akmana Field Party prospected the tributaries of the Arrabundio and then trekked across a spur of the Central Mountain Range to sample the Upper Karrawaddi River. Retracing their steps to the Arrabundio they then headed out across another spur of the Central Mountain Range to the Junction of the Yuat River with the Jimmi and Baiyer Rivers, again without finding gold in sufficient quantity. Returning to Madang at the end of December 1929, several of the party went back to Sydney to obtain instructions from the Akmana Gold Prospecting Company.

In mid February 1930 the second expedition quickly returned to their Mountain Base and on across the mountains to the junction of the Yuat with the Baiyer and Jimmi Rivers. They prospected south along the Baiyer River to its junction with the Maramuni and Tarua Rivers, where they established a palisaded forward camp naming the place ‘Akmana Junction.’ From this base they prospected along the Maramuni River and its tributaries, again without success. Finally they prospected the Tarua River south past the tributary which flows to Waipai, once more without success and on the advice of mining engineer Seale, it was decided there was nothing to justify further exploration. They had not progressed to any country on the southern watershed through which the early explorers and prospectors travelled to the Hagan Range and Wabag. The party returned to Madang, sailing for Sydney on 3 July 1930.

After leading the first expedition, Sam Freeman did not return and Reg Beazley became party leader of the second expedition, with Pontey Seale mining engineer, Bill MacGregor and Beazley prospectors and recruiters, and Ernie Shepherd in charge of transport and supplies, prospecting when opportunity arose. They had all served overseas during World War I with the AIF on the western front, in Egypt and the Levant and had previously been to New Guinea. In 1926 Freeman was near Marienberg with Ormildah drilling for oil; Shepherd was with Dr. Wade and R.J. Winters on their geological survey of a oil lease of 10,000 square miles (26,000 km2) in the Bogia and Nubio to Ramu region and up the Sepik River to Kubka 60 miles (97 km) above Ambunto. Beazley was drilling test sites for oil with Matahower in the lower Sepik and he and McGregor recruited labour on the Sepik and explored grass country to Wee Wak. Beazley also prospected the Arrabundio for gold and on his promising report to Freeman, Akmana Gold Prospecting Coy was floated in 1928.

The Akmana Gold Prospecting Field Party made contact with many peoples they called: grass country people, head hunters, pygmies, wig–men, Kanakas, Poomani. These contacts were often with the help of Drybow/Dribu, a leader and spokesman of the wig–men, a most intelligent man of goodwill, with a quiet authority that brought forth friendly cooperation. ‘We made a peaceful entry into this new country, establishing a reputation for fair trade and decent behaviour ... but gold was our interest and we had traced the rivers and tributaries as far as practicable where conditions and results justified the effort and found nothing worthwhile. In the many years since, there have been quite a few reports of prospecting parties in the area. But nothing of note has been reported: So we did not leave much behind, it seems.’ [4]

‘Members of the Akmana party donated wigs they had brought back to various museums. Two of them went to The Australian Museum, Sydney (from Beazley and Shepherd). Current records at the Australian Museum show that Beazley’s wig, described as “a cap composed of human hair from the headwaters of the U–at River, Central Mountains, Mandated Territory of NG”, was lodged on January 31, 1930, presumably on his quick visit to Sydney after the first expedition. Shepherd presented another wig to Father Kirschbaum, who wanted to send it to Germany. The wigs at The Australian Museum were later confused with some brought out of the Highlands 10 years afterwards by Jim Taylor during his Hagen–Sepik patrol, and wrongly attributed to him when put on display. Seale presented two wigs to the National Museum Canberra in 1930.’ [5]

The Territory of Papua and New Guinea

Following the surrender of the Japanese in 1945, civil administration of Papua as well as New Guinea was restored, and under the Papua New Guinea Provisional Administration Act, (1945-46), Papua and New Guinea were combined in an administrative union.

The Papua and New Guinea Act 1949 formally approved the placing of New Guinea under the international trusteeship system and confirmed the administrative union under the title of The Territory of Papua and New Guinea. The act provided for a Legislative Council (established in 1951), a judicial organization, a public service, and a system of local government. A House of Assembly replaced the Legislative Council in 1963, and the first House of Assembly opened on June 8, 1964. In 1972, the name of the territory was changed to Papua New Guinea. Australia's change of policy towards Papua New Guinea largely commenced with the invitation from the Australian Government to the World Bank to send a mission to the Territory to advise on measures to be taken towards its economic development and political preparation. The mission's report, The Economic Development of the Territory of Papua New Guinea, published in 1964, set out the framework upon which much of later economic policy, up to and beyond independence, proceeded.

Independence

Elections in 1972 resulted in the formation of a ministry headed by Chief Minister Michael Somare, who pledged to lead the country to self-government and then to independence. Papua New Guinea became self-governing on December 1, 1973 and achieved independence on September 16, 1975. The 1977 national elections confirmed Michael Somare as Prime Minister at the head of a coalition led by the Pangu Party. However, his government lost a vote of confidence in 1980 and was replaced by a new cabinet headed by Sir Julius Chan as prime minister. The 1982 elections increased Pangu's plurality, and parliament again chose Somare as prime minister. In November 1985, the Somare government lost another vote of no confidence, and the parliamentary majority elected Paias Wingti, at the head of a five-party coalition, as prime minister. A coalition, headed by Wingti, was victorious in very close elections in July 1987. In July 1988, a no-confidence vote toppled Wingti and brought to power Rabbie Namaliu, who a few weeks earlier had replaced Somare as leader of the Pangu Party.

Such reversals of fortune and a revolving-door succession of prime ministers continue to characterize Papua New Guinea's national politics. A plethora of political parties, coalition governments, shifting party loyalties and motions of no confidence in the leadership all lend an air of instability to political proceedings.

Under legislation intended to enhance stability, new governments remain immune from no-confidence votes for the first 18 months of their incumbency.

A nine-year secessionist revolt on the island of Bougainville claimed some 20,000 lives. The rebellion began in early 1989, active hostilities ended with a truce in October 1997 and a permanent ceasefire was signed in April 1998. A peace agreement between the Government and ex-combatants was signed in August 2001. A regional peace-monitoring force and a UN observer mission monitors the government and provincial leaders who have established an interim administration and are working toward complete surrender of weapons, the election of a provincial government and an eventual referendum on independence.

Although close relations have been maintained since peaceful independence and Australia remains the largest bilateral aid donor to Papua New Guinea, relations with Australia have recently shown signs of strain. While on a state visit in March 2005, Prime Minister Somare was asked to submit to a security check and remove his shoes upon arriving at the airport in Brisbane. Despite demands from the PNG government that Australia apologize, the latter refused. Additionally, problems have arisen with regard to Australia's latest aid package for the country. Valued at A$760 million, the program was to tackle crime and corruption in PNG by sending 200 Australian police to Port Moresby and installing 40 Australian officials within the national bureaucracy. However, after the first detachment of police arrived, Papua New Guinea's high court ruled that the arrangement was unconstitutional, and the police returned home. A new arrangement, by which only 30 officers will serve as a training force for the local force has been described by the Australian foreign minister as "second-best".[6]

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar